Why do anti-vaxxers have any traction in the modern world? Their opinions fly in the face of all common sense and scientific fact. For that matter, let’s apply the same question to climate change deniers, anti-gun control advocates or people who believe the moon landing was staged.

Data doesn’t sway them, scientific method doesn’t sway them, expert opinion doesn’t sway them. They are steadfast in their belief that their Google search is superior to the body of evidence accumulated over the years by people who make these matters their life’s work.

If there were a few such people, this would be a mildly interesting pig-headed phenomenon, but it’s not a few people. It is a mass movement of such volume that reduced vaccination rates are seeing the return of diseases that had been virtually eliminated. The World Health Organisation recently listed “Vaccine reluctance” as one of the top ten threats facing world health.

The proliferation of social media seems to correlate with the rise of outlandish and untenable positions, and it is easy to point the finger, but until we understand how social media spreads contagions of bad ideas it is hard to come up with a solution.

Evolutionary Biologist, Richard Dawkins was the first to coin the term “meme”. In Dawkins view, a meme is an idea that can be spread and is subject to the same rules of evolution that govern biological proliferation. Instead of living in a growth medium like bacteria, Memes live in brains. They do not replicate through sexual selection, but through selective sharing to other brains.

Some memes replicate for a short period of time (the kid swinging a broom as if its a lightsaber) whereas others survive beyond the biological life of their creator (XXX was ‘ere graffiti). There are a number of factors that determine meme survival, but their mechanism of replication, their complexity and the desirability of being replicated all play a role.

Ease of Transmission

Simple ideas are easier to spread than complex ones. Gun control is a great example. Most people will tell you unequivocally that the US Constitution’s Second Amendment;

“Guarantees the right to bear arms”

It says no such thing, actually it says;

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The words “well regulated” are right there, but they’re conveniently forgotten and replaced with the briefer and pithier “right to bear arms”.

This is an evolutionary battle between two competing ideas, the one that resides int he most brains will win. The “right to bear arms” is easy to remember, fits on a bumper sticker, does not use parenthetical commas or split infinitives. The grammar is better, the meaning is clearer and there are fewer words. The wording of the actual second amendment has none of these virtues.

I ran a quick age of reading calculator over both sentences. The actual Second Amendment requires 16 years of formal indication to be easily comprehended on first reading. The shorter version needs only 2 years of formal education to gain the same level of understanding.

The “right to bear arms” is a superior and simpler piece of English and therefore far more likely to be the winner in the meme selection race.

When Donald Trump claimed that he was “the Ernest Hemmingway of 150 characters”, I don’t think he was referring to the fact that he is also a crass buffoon, rather he was boasting of his prowess at distilling complex ideas into very simple memes that can be shared, liked, retweeted, and used in arguments around the water cooler at work.

The marketplace of ideas used to require memes to cross at least some basic plausibility threshold of peer review and expert acceptance, but social media has now opened an entirely new channel of meme replication.

“Vaccines cause Autism”

“If the bad guys have guns, then you need one to protect your family”

These ideas exist in a world beyond review. They can be retweeted millions of times, then attached to a picture of a flag or a sick child or some other similarly emotive image and retweeted another million times. Now tens of millions of brains are carriers of the meme. Not all of them will choose to share the meme, but it has certainly survived to the second generation. In truth, there are several orders of magnitude more people who will see the “vaccines cause autism” meme than will read the scientific papers that show the facts.

But that is just the start of the story, now that tens of millions of brains are carrying the “vaccines cause autism” meme, why are they not all inoculated by experts who can pass on the actual facts.

Why don’t we trust experts anymore

This goes to the core question; we can see how a simple incorrect message is easier to spread than a complex accurate one, but why are experts no longer persuasive.

We live in the most enlightened time in human history, never before have we known so much about the quantum realm, the genome, and epigenetic interactions and the forces that control the fate of the universe, yet more people now consult with astrologers, buy homeopathic remedies, and try and use mega-doses of vitamin C to cure cancer.

It is my belief that knowledge acquisition has now outstripped education. In the 1900s when it was the internal combustion engine that revolutionised the way we live as a species, this was a revolution that could be understood. Every school kid could grasp how heat and pressure could be translated into movement, and everyone knew someone who was a hobbyist, tinkering with the new technology in their own backyard.

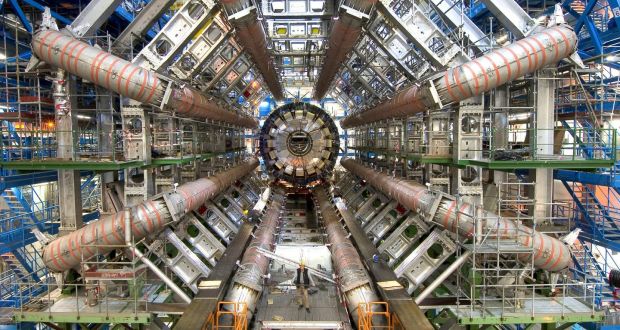

How many people truly understand how a CRISPR machine works in gene editing, or how the CERN supercollider relates to matter and the origins of the universe, or how the CPU in their iPhone uses tiny switches which in a combination of off and on instructions make Siri talk to you.

We have to trust experts that these things are true, and with trust goes faith, and why is my faith in the truth of global warming more valid than your faith that its a hoax perpetrated by China?

This question is straight out of a post-modern undergraduate university playbook. Question everything, and eventually, the construct itself will fall under the weight of uncertainty. When I began my undergraduate studies, this post-modern toolkit was something we amused ourselves with over beers at the pub. You can literally argue that black is white (or at least that the concepts of black and white are so subjective to the individual that to try and differentiate them is meaningless).

This type of argumentative strategy is also contagious and has spread through social media like a viral phenomenon. It allows ill-informed people to raise their status above those who are informed. When a leading immunology researcher is asked, “can you list every ingredient contained in every preparation of every vaccine produced?”, the immunologist looks stupid if they cant, and boring if they can.

Postmodern questioning places an unbearable asymmetry on bullshit, those who know what they are talking about would have to spend several lifetimes responding to every piece of bullshit that is spread virally, and even if they did no one would read their complex and correct replies anyway.

So bullshit flourishes in the absence of rational debate.

The solution to all of this will not be simple, and I do not pretend to have answers. However, science needs to learn how to become sexy, how to cut through and how to simply and virally respond to the bullshit merchants. Every child in the western world that dies of a disease for which vaccination is available is a victim not of a viral epidemic, but of a bullshit epidemic. We need our medical and psychological colleagues to be putting their minds to how to treat this modern epidemic.